The West's Best Waterfalls

Spring is the best time to visit these must-see waterfalls in Western states.

Trickles or torrents, sheer plunges or rocky chutes, mountain cataracts or desert gushers, waterfalls draw us into their multi-sensory spectacle. We delight in the sight and sound of their tumbling waters, inhale their freshness, even feel their tingling spray on our faces. They can soothe us and, some say, improve our mood by bathing us in negative ions. For naturalist John Muir, their song helped him "get as near the heart of the world" as he could.

What makes a waterfall noteworthy? Height, width, and volume all count, says expert Bryan Swan of the World Waterfall Database and Northwest Waterfall Survey. Based on his criteria and other factors—such as ease of visiting and the thoroughly unscientific observation that they're darn pretty—here are ten must-see falls in the West.

Yosemite Falls, Yosemite National Park, California

Even in a Sierra Nevada valley famed for sending water over cliffs—from brawny Vernal to lithe Bridalveil—Yosemite Falls astounds. Hurtling 2,425 feet earthward in a series of free falls and tumbles, California's highest waterfall is at maximum flow in May or June. Visitors crowd the easy, mile-long Lower Yosemite Fall Trail to its base to revel in the drama of drenching mist and chest-rumbling sound. But the falls can also bewitch quietly, especially on clear nights when the moon is full and the water level is high. "That's when lunar rainbows—moonbows—materialize in the spray," says Sacramento photographer Beth Young. "Long-exposure photos capture them best, but even with the naked eye you'll see them faintly."

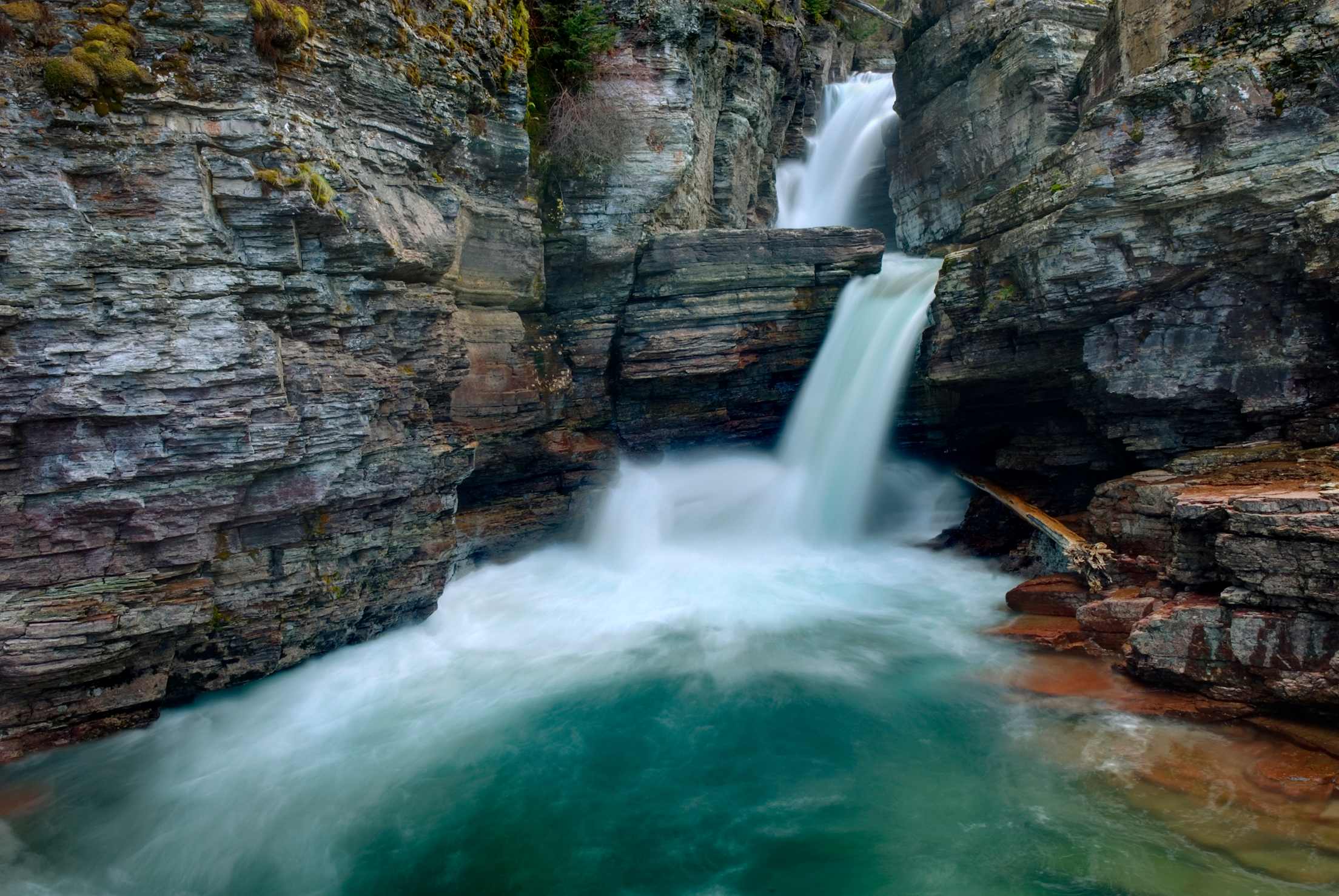

St. Mary Falls, Glacier National Park, Montana

This 35-foot beauty is one of the West's most colorful falls. Sunlit glacial sediment turns St. Mary's waters a brilliant teal as they tumble down two tiers of brick-red rock into a pool capped with white froth. A 2015 wildfire ravaged the surrounding forest, temporarily closing the trail to the falls (1.7 miles round-trip), and now hikers to St. Mary—and to 50-foot Virginia Falls about a mile beyond—experience an utterly transformed landscape. But that isn't all bad. "The fire opened incredible lake and mountain views," says Interpretive Park Ranger Lee Rademaker. "The blooms of wildflowers have been spectacular, and patches of lodgepole pine seedlings are already five inches high."

Bridal Veil Falls, Provo, Utah

Dozens of falls throughout the United States are named Bridal Veil, but few are as fetching as this beauty 10 miles northeast of downtown Provo. The tallest waterfall in Utah, it descends a whopping 607 feet in a pair of plunges and a long, rocky cascade that fans out like its namesake shroud. In 2015, the spring-fed, year-round falls and surrounding land were purchased by Utah County from the family that had long owned them, and the last remnants of a defunct aerial tramway and an abandoned restaurant near the top of the falls were removed. The waterfall's base is easily reached with a stroll through Bridal Veil Falls Park, a shady haven by the Provo River that's popular for picnics and—no surprise—wedding proposals and engagement photos.

Shoshone Falls, Twin Falls, Idaho

At full spring-season force, with water thundering 212 feet downward from a 900-foot-wide rim, Shoshone Falls is a display worthy of its nickname: "Niagara of the West." Upriver irrigation greatly diminishes its flow later in the year, but even then, this Snake River cascade 130 miles southeast of Boise captivates as it streams down a facade of rhyolite lava that's at least 8 million years old. It's easily viewed from adjacent Shoshone Falls Park, but for a better sense of its girth and horseshoe shape, walk from the parking area along the paved Snake River Canyon Rim Trail to the downriver lookout about a quarter-mile away. From there, you can also spot an artifact from a 1974 spectacle of an entirely different sort: the earthen launch ramp that daredevil Evel Knievel used in his unsuccessful (and fortunately nonfatal) attempt to jump the mile-wide Snake River Canyon on a rocket-powered motorcycle.

Multnomah Falls, Columbia River Gorge, Oregon

Roughly 75 falls grace Oregon and Washington's "Waterfall Alley," the Columbia River Gorge. Plenty are dazzling, but only Multnomah—30 miles east of Portland—ranks among the Pacific Northwest's most sublime meetings of water, rock, and forest. Though the 620-foot-tall, year-round cascade was assaulted by wildfire last summer, leaving much of its trail system still closed, the lower viewing platform is scheduled to reopen by March and once again offer a thrill, especially during peak flow in winter and spring. Gazing at the 542-foot upper tier and 69-foot lower tier as they roar downward, give silent thanks that Multnomah survived an earlier, and potentially more cataclysmic, threat: a 1915 scheme to make Oregon's tallest waterfall a decidedly unsublime power source for a lumber mill at its base. Instead, the site became a public park later that year.

Grand Falls, Leupp, Arizona

Willy Wonka himself could not have concocted a scene of more surreal beauty than Grand Falls, also known as "Chocolate Falls." Laden with silt from the 150-mile journey across the Painted Desert, the ruddy brown waters of the Little Colorado River tumble down 185 feet of basalt terraces like chocolate milk spilling down a stairway. Unlike Mr. Wonka's fictional factory, however, the falls don't run all the time. Roaring to life during snowmelt season in March and April and after summer monsoon rainstorms, they're nothing but a trickle the rest of the year. You'll find them on Navajo land, a 66-mile drive northeast of Flagstaff, largely on paved road plus about nine miles of dirt.

Kings Canyon Waterfall, Carson City, Nevada

In the driest, most waterfall-challenged state in the union, Kings Canyon seems an especially precious gift of nature. Fed by snowmelt so pure it requires little processing before becoming Carson City drinking water, the year-round 25-foot cascade splashes into a creek that winds like a greenery-fringed ribbon through parched and rocky sagebrush terrain. Johanna Foster loves the waterfall and knows it well: She is one of the volunteers who maintain the half-mile trail that switchbacks 175 feet up to its base from a parking area just west of downtown. "I've probably been there 100 times, enjoying the cool spray on a hot day, the lush vegetation, and the wonderfully fresh smell," she says. "And every time I think the same thing: 'I can't believe I'm in the desert!'"

Burney Falls, McArthur–Burney Falls Memorial State Park, California

Gazing at the sapphire water beneath 129-foot-high Burney Falls, a plunge nestled deep in a canyon of century-old firs and pines 100 miles south of the Oregon border, it's hard to imagine that such enchantment was born in fiery cataclysm. The 100 million gallons of water that gush here every day of the year, echoing through the surrounding forest, come from underground springs. Rain and snowmelt are held in a geologic substratum of porous basalt created during violent volcanic eruptions 1 million years ago. "The most magical thing is that water doesn't just come over the lip but pours out of the rock face itself," says local angler Andrew Harris, who has often walked the half-mile path from the parking area to the pool to cast for native rainbow trout. Swimming isn't allowed, but you can go for a dip at Lake Britton, just two miles away.

Snoqualmie Falls, Snoqualmie, Washington

They say power seduces, and that is certainly the case with Snoqualmie Falls. Situated a short drive off I-90, about 25 miles east of Seattle, this stunner—one of North America's most powerful waterfalls by volume and height—squeezes the Snoqualmie River through an andesite chute and then dives 268 feet. Its intensity has drawn the attention of hydro engineers since at least 1899, when they first tapped it and reduced its flow. Managed by Puget Sound Energy, the waterfall is still impressive from both the upper and lower viewing platforms, especially when it swells with rain or snowmelt. "We're sitting on solid rock here," says Alan Stephens, general manager of the Salish Lodge & Spa, which overlooks the rim. "But on big flow days, we can even feel the rumble indoors."

Havasu Falls, Supai, Arizona

A waterfall can give us more than sensory thrills. Remote Havasu Falls is undeniably impressive: a roaring cataract of luminous turquoise that lunges from red desert cliffs into natural travertine pools 90 feet below. Fed year-round by a limestone aquifer, it lies deep in the Grand Canyon on the tribal lands of the Havasupai—the "people of the blue-green water." Visitors must secure a camping or lodging reservation for Supai Village, then prepare for 20 miles of hiking, out and back (or a helicopter ride plus four miles of hiking). For those who make the trek, the falls are a miracle of beauty and strength. No less miraculous are the village's cultivated plots of corn, beans, and squash thriving in the harsh desert. For the Havasupai, the waterfall's bounty gives life.