History of Hearst Castle

A newspaper tycoon crowned an unassuming California hilltop with the palace of his dreams.

William Randolph Hearst never called it Hearst Castle. To him, the palace above the Pacific was La Cuesta Encantada (the Enchanted Hill) or, simply, the ranch at San Simeon.

Whatever you call it, the opulent retreat was born in 1919. Hearst was 56 and wildly famous: a press baron, a film producer, a genius at making money and at spending it. He had dreamed of building a grand home on a piece of his family’s land in coastal San Luis Obispo County, and he hired architect Julia Morgan to make the dream real.

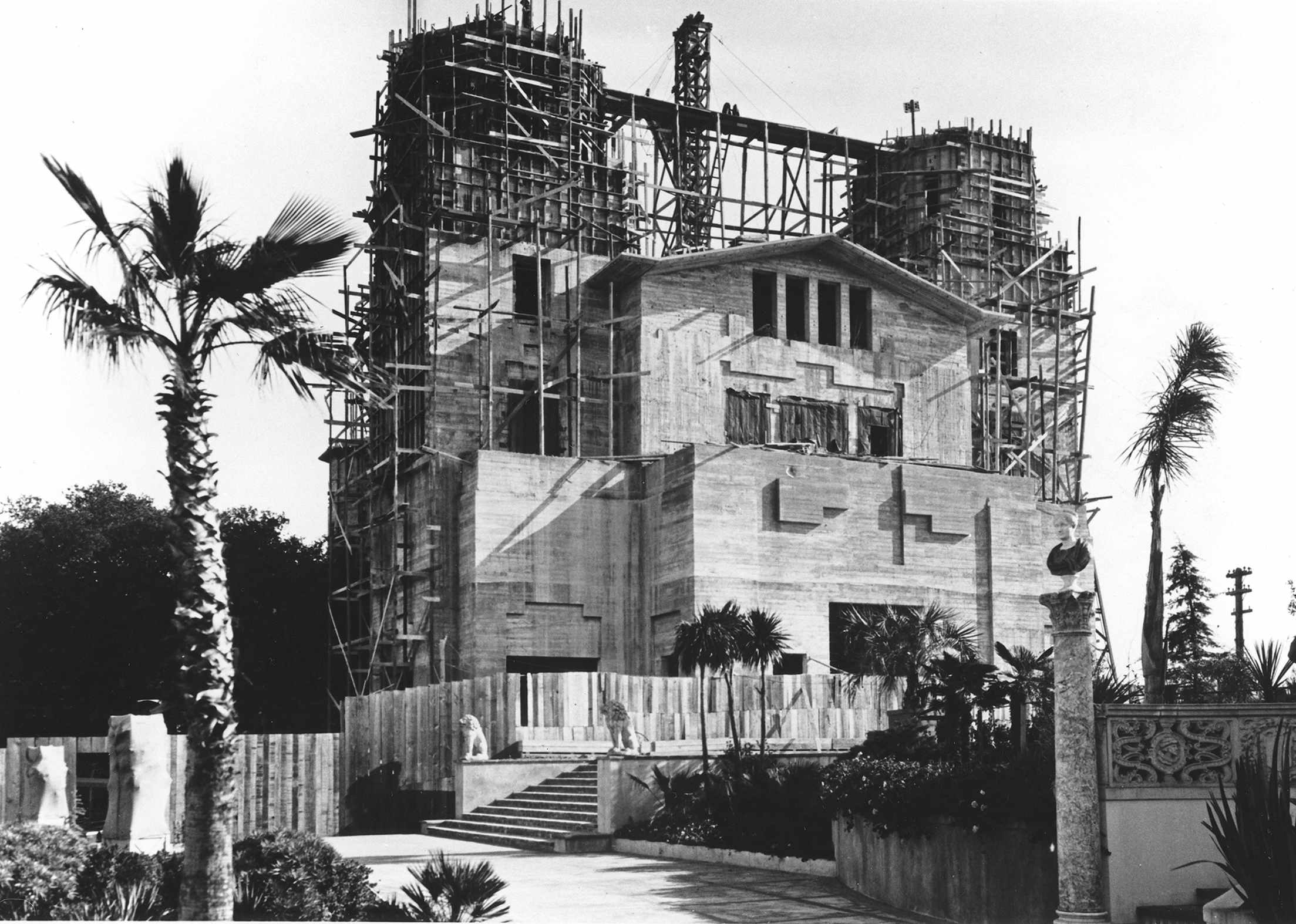

It wasn’t easy. All the tools and materials—lumber, cement, even a rock crusher—were shipped to the San Simeon village dock, then hauled up a steep dirt road to the construction site.

Hearst thought the project would take two years. Instead, construction went on for decades. But in the end, he and Morgan created a masterpiece—with 38 bedrooms, 42 bathrooms, and lavish public rooms—topped by cathedral- inspired towers. Hearst then filled the Ranch with famous guests such as Cary Grant and Bette Davis.

After Hearst’s death, his family donated the property to the state. Guide Scot Steck advises first timers to take the Grand Rooms Tour to see the public spaces, then return for the Upstairs Suites Tour. “You’ll see where Hearst lived,” Steck says. And one glance at the tycoon’s suite will make you wish you could live like he did, if even for a brief moment.

History and Hollywood Allure

Born in 1863, Hearst was a native San Franciscan who transformed the millions milked from the family silver mines into publishing gold. By the time he first laid plans for the Castle on the ridge of a favorite childhood campsite 90 miles south of Monterey, W.R. was 56 years old. He had already gobbled three or four lifetimes' worth of adventures and was hungry for more. Hearst was a Harvard dropout with a voracious lust for antiquities. He had a society wife and five sons, but he lived openly for 30 years with a mistress 35 years his junior, film star Marion Davies. He was a tycoon who'd begged money from his mother, a large man with a tinny voice, a presidential hopeful who dreaded public speaking. He was a populist who loved animals more than people, a founding father of tabloid journalism who banned sex and scandal from his movies.

Homes to Hearst (and he had several) were all spectacular themed sets where he could stash his treasures, wow guests, and gather cronies to plot his next business or political move. His father, George, another man of stubbornly outsize appetites, once wrote of young Will, "When he wants cake, he wants cake and he wants it now. I have noticed that, after a while, he gets the cake."

"You have to understand, it was a different time," said former Hearst employee Wilfred Lyons in an interview in 2003. In the 1930s, when Lyons and his late wife were fresh faced and affianced, both worked for Hearst at the Castle and had the time of their lives. As part of his job there, Lyons worked many of the parties over the years, crisp and tan in his bow tie and white jacket. Regulars in the 1930s included Clark Gable, Myrna Loy, Bing Crosby, Charlie Chaplin, Irving Thalberg, and Norma Shearer. "The movie people were always there," Lyons said. "My favorite was Cary Grant. He stopped on a couple of occasions to visit at the gatehouse with us. We'd talk about the movies, life—everything. He was great fun." Sometimes, apparently, too much fun; one day Grant nearly got himself kicked off the property permanently when he and Will Jr. took a small plane up above the estate and, as a prank, bombarded the hangar's roof with sacks of flour. When they returned, Grant's bags were packed and waiting for him by the front door—W.R.'s not-so-subtle signal to drunken or philandering or otherwise boorish guests that it was time to go.

"There was a lot of hanky-panky in those days," according to Lyons, who refused to name names. "But Mr. Hearst was very strict. If you did something he didn't like and he found out, you didn't get invited back." A glass or two of wine was served with dinner but cocktails were strictly rationed, probably to rein in Davies, a charming but determined alcoholic.

The staff addressed their employers deferentially as "Mr. Hearst" and "Miss Davies," but otherwise the tone of the place was deliberately unpretentious, Lyons says, despite the gilt and glamour. Visitors and servants enjoyed the same lavish menus of ranch-reared steak and poultry, or Alaskan salmon flown in fresh. Guests dined family style with Hearst in his grand dining hall, using camp china, heavy antique silver, and paper napkins; they reached around crystal goblets to get to the ever-present mustard and ketchup bottles in the center of the table.

Nobody strayed far from the house at night. "It sounded like you were in Africa out there," Lyons recounted. Hearst's collection of carnivores, including lions, leopards, and polar bears, were kept in separate locked enclosures, but the less dangerous exotics, among them kangaroos and yaks, freely roamed the hills.

Son of the West, King of the Castle

In Hearst's mind, to have the compound of his dreams, money was never a hurdle. When a 100-year-old oak stood in the way of one of his design whims, the tree was moved (at a cost of about $40,000), rather than destroyed; towers were demolished and rebuilt as the scale of the building expanded; swimming pools were ripped out and replaced twice. With all the comings and goings of animals, guests, workers, and priceless art, it's no wonder, said Lyons, that the lord of the manor was sometimes testy.

On one night Lyons described a driver was late getting back from Hollywood with a movie to be screened that evening. In his rush to deliver it, he nearly ran over Hearst's cherished hound, Helen. "We heard W.R. yelling in his high voice, 'You're fired, you're fired, you almost hit the dog,' " Lyons recalled. "Miss Davies was running along behind, saying, 'You're not fired, you're not fired, keep doing what you were doing.'"

Davies was always the funny mollifier, Hearst's true love, muse, and confidant. Of all the fictions mixed with facts in Citizen Kane, the one that reportedly cut Hearst deepest was the insinuation that Davies—thinly disguised in the movie as Kane's second wife, a blond alcoholic—was devoid of talent and dependent on Hearst to prop up her career. Even Orson Welles said the opposite was true. "Marion Davies was one of the most delightfully accomplished comediennes in the whole history of the screen," the director wrote in a 1975 foreword to Davies's posthumously published memoir. "She would have been a star if Hearst had never happened."

The man who could and did buy everything saved his Castle's best view for himself. It's the vista from his bedroom window of the roaring edge of the Western frontier, a dividing line of crashing waves and swirling foam where the Pacific flirts with the weathered hills. Hearst was a true son of the West, and even those who hate much of what he stood for have to admire his exuberance and undying faith in the future. "Many Easterners never clearly understood what made Pop and his fellow Westerners tick," Will Hearst Jr. once wrote. "[His] America was yet to be discovered—a land and people of incalculable hope amid endless horizons."

Morgan's Magic

Like her client, Julia Morgan was a demanding workaholic who lived on coffee and chocolate bars and spent 28 years of weekends overseeing construction at San Simeon. She kept busy in San Francisco during the week, designing at least 700 other buildings in her lifetime. Hearst's oversize abode isn't the only place to get swept away by the architect's pioneering work.

In 1897, when Julia Morgan first applied to the architecture school at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the admissions officials hadn't bothered to conceive of the notion. A woman architect? But why?

Soaring churches, groundbreaking women's clubs, hundreds of homes both grand and spare, sumptuous swimming pools, and Hearst Castle are Morgan's eloquent retort.

All this from a person who looks in photographs like a timid soul. Owlish spectacles overshadow her features and her petite frame appears featherlight. But Morgan (1872-1957) possessed the spark to spend two years in Paris fighting for—and winning—entrance to the world's most prestigious school of architecture. "She had to have enormous persistence," says Nancy Loe, archivist for the Julia Morgan Collection at Cal Poly-San Luis Obispo.

Her creativity flowered mainly in California and embraced many styles—arts and crafts, Gothic, Italianate, and others. Despite this diversity, one word unites her eclectic oeuvre: romantic.

It's not so much an architectural label as pure, heartfelt description. See for yourself at these treasures:

Morgan insisted that her designs complement the surrounding landscape. Asilomar, a retreat/conference center in Pacific Grove run by the California State Parks, is the apex of that ideal. Her buildings soar with open ceilings, redwood beams, stone fireplaces, and earthy elegance befitting the cypress-strewn, ocean-side site.

The Berkeley City Club is a six-story neo-Gothic fantasy of garden courtyards, intimate alcoves, and dramatic fireplaces. "It was her castle," says Lynn Forney McMurray, Morgan's goddaughter. Today, the club is open to the public for dining.

Oakland's Chapel of the Chimes, a crematory and columbarium, glows with the golden sunlight that filters through its stained-glass ceilings. Morgan crafted a spiritual maze of 150 rooms, no two exactly alike. Visitors are welcome daily 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Morgan had been in practice for only two years when she accepted the monumental assignment of repairing San Francisco's Fairmont Hotel, which had sustained severe damage in the 1906 earthquake and fire. The Fairmont was the first hotel in the city to reopen (with a party that featured 600 pounds of turtle and 13,000 oysters).

Frugal travelers with an imagination will enjoy the Hacienda, a mission-style ranch estate where the Hearst family entertained celebrity pals. Today the property, in remote Jolon, California, is owned and surrounded by Fort Hunter Liggett army base.

Let AAA Complimentary Travel Agents plan your trip. It's a free benefit for AAA Members.