What Cities Are Doing to Make Roads Safer

Cities across the West are paving the way for safer streets for everyone.

The United States is grappling with a rapid rise in traffic fatalities over the last two years. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates that 42,915 people died in motor vehicle crashes nationwide in 2021—a 16-year high. In California, traffic deaths rose nearly 11 percent, while Nevada and Utah both saw more than a 20 percent increase over the already high number of 2020 fatalities. When compared to 49 other high-income nations, the U.S. ranks 41st in traffic fatalities with 12.67 deaths per 100,000 people, far behind Norway's 2.12 deaths per 100,000 people, according to the World Health Organization.

This increase hasn’t affected all road users equally. Pedestrian and cyclist fatalities account for nearly 20 percent of all traffic deaths each year. Last year, drivers struck and killed an estimated 7,485 pedestrians, the most fatalities in 40 years and a 46 percent increase over the yearly average for the last decade, according to a report from the Governors Highway Safety Association. Crashes are one of the leading causes of death for people ages one to 25, and people walking in low-income areas are nearly three times as likely to be fatally struck as people in high-income areas, according to the nonprofit Smart Growth America.

While many factors influence safety on our streets—driver behavior, speed limits, vehicle design, and more—cities around the West are now looking at how roadways are designed to help turn the tide and make roads safer for all users, especially the most vulnerable. The recent $1 trillion infrastructure act is providing much-needed funding for improvements, while also pushing cities to reduce traffic fatalities and serious injuries to zero by adopting a safe system or Vision Zero approach. Under this method, streets are designed to protect all people, even when someone makes a mistake.

“We are humans, and at some point we’re going to mess up,” says Offer Grembek, a researcher and codirector for the University of California at Berkeley’s Safe Transportation Research and Education Center (SafeTREC). “We need to design for these human mistakes so that when something does go wrong, the system is prepared to contain or control it.”

Many cities in the West have already adopted these principles, including Anchorage; Fremont, California; Portland; San Francisco; Tempe, Arizona, and Watsonville, California. To get a glimpse of the future, we can look at the changes that are taking shape now.

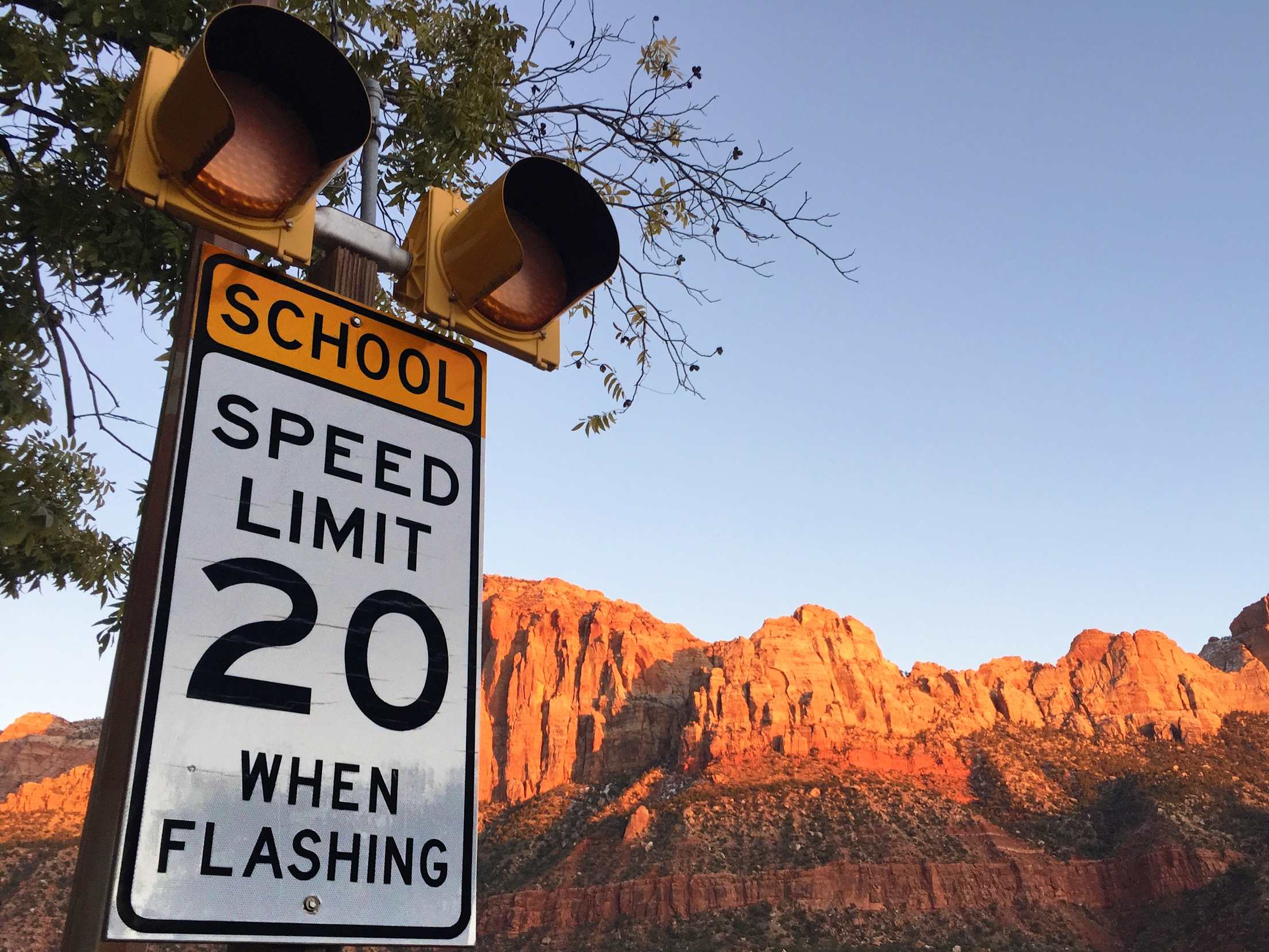

Slower Speed Limits

Speeding—exceeding posted limits or driving too fast for conditions—is a contributing factor in more than a quarter of all traffic fatalities. Even small increases in speed can raise a driver’s risk of severe injury or death, according to crash tests performed by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, and Humanetics.

But on city streets in particular, speed limits may be lower in the future. Controlling speed is one of the most important methods for reducing serious injuries and fatalities. Slower speeds allow drivers to stop and avoid crashes more easily, which reduces the number and severity of crashes. A driver going 30 miles per hour when they hit a pedestrian has a 45 percent chance of killing or seriously injuring them, but at 20 mph, the chance drops to 5 percent, according to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

Fremont, Portland, and Seattle have reduced their speed limits across city streets. Portland lowered speed limits from 25 to 20 mph on nearly all residential streets, which make up more than 70 percent of the city’s approximately 2,100 miles of streets. A Portland State University study looked at the impacts of the speed limit decrease and found that there was a drop in the probability of people driving faster than the speed limit, with the greatest decrease in people driving faster than 35 mph.

After Seattle implemented speed management strategies, including reducing speed limits on arterial streets to 25 mph and residential streets to 20 mph, traffic fatalities decreased by 26 percent from 2017 to 2018. San Francisco is also introducing lower speed limits, starting with new 20 mph limits across the Tenderloin, a hotspot for traffic fatalities.

“Reducing the speed limits from 25 to 20 actually has a huge impact on the survivability of a crash,” Grembek says.

Traffic Calming

A speed limit sign alone is often not enough to slow traffic significantly, but adjusting the design of the roadway can encourage drivers to ease off the pedal and pay better attention to their surroundings. Engineering changes to roadways have consistently been found to be the most effective interventions at reducing pedestrian injuries and deaths.

“Policy makers need to think beyond enforcement to control speeds and should consider infrastructure changes based on road type to calm traffic flow appropriately so that posted speed limits are followed,” says Jake Nelson, director of Traffic Safety Advocacy and Research for AAA.

Traffic calming measures such as reducing the width of roads, adding raised crosswalks, and installing speed humps are some of the tools cities are utilizing to naturally reduce drivers’ speeds. As part of its Vision Zero Safe Streets plan, San Francisco added more than 200 traffic calming devices in 2021, including traffic circles, speed humps (and their larger cousins, speed tables), and left-turn traffic calming devices such as bollards and rubber curbs.

“Traffic calming sends the message that ‘motor vehicles don’t exclusively own the roadway,’ that other modes have equal rights,” the FHWA explains on its website. Studies show that traffic calming increases walking, bicycling, and transit use. It also improves safety where it matters most: Nearly three out of four pedestrian fatalities happen outside of intersections, which means the speed people drive between intersections is crucial for the safety of people walking, using a mobility aid, or biking.

Across Fremont, the city narrowed lanes that were once as wide as the lanes on Interstate 880 down to 10 feet wide from the previous 12 to 14 feet. The narrow lanes “naturally brought travel speeds down and created, we think, a greater sense of care in the people that are driving,” says Hans Larsen, director of Fremont’s Public Works Department. “When streets have multiple wide lanes, we have seen a greater frequency of high speed crashes occurring due to reckless driving, where speeds have been determined to be at ‘freeway speeds’ in the range of 65 to 80 miles per hour.”

By narrowing lanes for traffic, Fremont was also able to add bike lanes, install buffers on existing bike lanes, and make more room for pedestrians to safely move and cross. The changes may also benefit drivers: Studies have shown that reducing lane widths does not increase congestion or injuries, even when bike lanes are added, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration.

More Shared Space

“Street design in the last 50 years has been oriented toward moving cars fast and efficiently,” Larsen says. But cities, particularly in the West, are now shifting from prioritizing vehicle traffic to a more holistic approach that’s often referred to as “complete streets.” From Fremont to Seattle, cities are widening sidewalks, landscaping to buffer traffic, and installing bike lanes to make pedestrians and cyclists feel more welcome and increase their visibility to drivers.

Portland, already widely known as one of the most bike-friendly cities in the nation, is now aiming for more than a quarter of all trips to be made on a bike by 2030. While classic white-striped bike lanes can go a long way, “we’ve found that a variety of infrastructure works best to provide bike routes that will be comfortable for a variety of people,” says Dylan Rivera, spokesperson for the Portland Bureau of Transportation. The city has 162 miles of bike lanes, 85 miles of paths, and 94 miles of Neighborhood Greenways—slow streets that prioritize pedestrians and bicyclists and often divert vehicle traffic—to encourage everyone from commuters to kids to pedal, roll, or walk. Last year, no one on a bike died in a collision in Portland, a success story few other cities have matched.

Similar, safer, better-connected, and more inviting bikeways are a big reason that biking grew by 184 percent in San Francisco between 2006 and 2017, according to the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. An estimated 82,000 bike trips take place in San Francisco each day, and the city is slowly giving space back to people instead of cars. More than two miles of bustling Market Street is now closed to private vehicles to improve safety and make room for the thousands of people who walk, use mobility aids, ride transit, and bike along the street every day. An additional 92 miles of future bikeways are also planned across the city to continue growing the network.

Many design changes, including street landscaping and the slow streets and parklets that popped up early in the pandemic, also improve the surrounding community, providing space for recreation and gathering, reducing crime, improving air quality, and generating less noise.

While we can’t predict exactly what streets in our cities and neighborhoods will look like in the coming decades, the experts we spoke with are hopeful that we’re moving in the right direction.

“At every level there is policy encouragement—within the Bay Area, California, and nationally—to take bold action to reduce the [number] of people who are getting killed and seriously injured [on our streets],” says Larsen.